Key highlights

- The idea that addressing – and investing in – social issues is good for business, is becoming more widely shared by investors

- Social considerations, are important factors not only in corporate performance—making

companies more diverse, stable and resilient, but also in social improvement—making supply chains and communities more robust - Nordea’s Global Social Empowerment Strategy sees an investment opportunity in the gap between social needs and available solutions

- Active managers with the right analytics and engagement can leverage this gap to deliver returns and responsibility

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) investments are more popular than ever with assets expected to reach $53 tn within the next four years, accounting for one-third of global AUM.1 As the trend builds, investors are expanding their horizons beyond the ‘E’ to consider factors that fall within the ‘S’ category — e.g. labour rights and standards, health and safety, human capital development and diversity. The corporate reputational and regulatory risks companies face can cause lasting damage and drive down stock value, while ESG leadership can provide upside. An increasing body of data suggests there is a link between ESG and financial performance.2

The idea that investing in people and working to address social issues is good for business is shared by investor

groups across the globe (e.g. investor statement acknowledging long-term value creation is ‘inextricably tied’ to stakeholder welfare signed by 336 institutional investors representing over USD 9.5 tn).3

The opposite is also true, that companies with weak records on human rights or labour practices are likely to suffer from increased supply-chain disruptions, affecting both operational performance and brand reputation.4

Social considerations, the S in ESG, are therefore important factors not only in corporate performance—making

companies more diverse, stable and resilient, but also in social improvement—making supply chains and communities more robust.

ESG considerations in investing have taken on particular relevance in light of the ongoing health crisis.

The ESG zeitgeist is here to stay

Certainly, if anything has taught us the importance of social stability and cohesion, it’s the outbreak of Covid-19. Every country, sector and individual has been impacted by the pandemic, which has highlighted the importance of examining the sustainability of global business models more closely. Covid has also been a good litmus test for investors to assess how resilient companies have been in the face of the crisis and how prepared they are for any future disruptions.

ESG considerations in investing have taken on particular relevance in light of the ongoing health crisis. The virus has had a profound impact on the global economy. The initial lockdowns imposed in response caused a collapse in the oil price, a broad-based sell-off in risk assets and an unprecedented suppression of economic output. In this environment, ESG investment solutions performed strongly, throwing an additional spotlight on the area.

The pandemic has not only highlighted in particular the social challenges that some business models are facing, it has also flagged the agility of companies which were able to adapt more easily to new ways of working and those whose businesses were able to thrive as they met pandemic challenges. For example, e-health provider Ping An has been particularly well-positioned for the rapid surge in demand for its services during the Covid pandemic. The company has been helpful in reducing the strain on hospitals during these difficult times. The number of new users on its digital platform rose nearly 900% in January 2020, over the prior month.

In addition to pandemic-driven investor focus, ESG has also taken on greater significance within the regulatory landscape, with new requirements to report on certain aspects of ESG – once solely voluntary but now mandatory – in many jurisdictions, including the UK, EU and Hong Kong (and the US likely to follow suit).5

Shifting toward the ‘S’

To date, the ‘E’ has dominated focus within the ‘ESG’ landscape, with environmental concerns like climate

change high on the list of investor priorities, while the ‘S’ has lagged. Regulation on ESG issues has overwhelmingly focused on the ‘E’ and the ‘G’ – something we also see in terms of the availability of corporate data. This is partly because social issues are slightly more difficult to define and are more qualitative in nature. This has been apparent even in terms of the disparity in the standards and ratings available to investors between the ‘E’, the ‘S’ and the ‘G’. The financial and investment world has identified a number of tools to measure and report environmental impacts, ranging from standardised methodology to measure carbon footprints all the way through to consistent reporting standards within corporate accounts (such as those being proposed by the TCFD, the Task Force on Climate-related Disclosures). Social reporting is lagging far behind this, with little consensus

yet reached on how or what companies should report.

But this is changing. Regulation is becoming more defined in terms of social issues and – as was the case with environmental reporting – social reporting is moving from the voluntary to the mandatory. In Europe, for

example, the European Commission is expected to issue a directive that requires human rights due diligence for

companies based (or with operations) in the EU.6 The EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR),

which came into force in March 2021, will require financial market participants to disclose on the sustainability

of their funds —including adverse impacts— with the first mandatory reporting required in July 2022.7 While

the EU Taxonomy regulation, which is building a framework by which economic activities can be assessed as

sustainable or not, is currently focused on identifying detailed criteria for environmental sustainability, its next

steps will be to address social criteria.

Social reporting is lagging far behind this, with little consensus yet reached on how or what companies should report.

Because investors must disclose the sustainability of their funds, the companies they invest in will be required to report the relevant information. This year, the European Commission adopted the proposed Corporate Sustainability Directive (CSRD), which will replace the current EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) in 2023, to require companies to provide sustainability information to investors, including social and employee impacts, respect for human rights, and anti-corruption and anti-bribery matters. With the Biden-Harris administration advocating for greater corporate disclosure on issues like human rights abuses, the US may not be far behind Europe.

Ratings agencies are also recognising the importance of ‘S’ considerations in issuer credit quality. Fitch specifically considers social ‘risk elements’ such as human rights, community relations, labour practices, exposure to social impacts and data security.8 While S&P, against the backdrop of the pandemic, has committed

to monitoring the effects of safety management and community engagement on credit quality over longer time horizons.9

Recent social justice movements and call-out culture emphasise how people are demanding more of the companies they invest in. Indeed, a report from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development underlines the fact that ‘investors are increasingly seeking both enhanced financial returns over time, and the societal alignment of their investments, to maximise financial and social returns’.10 This is particularly true among younger investors, who ‘were more attentive to the actions of companies in response to the Covid-19 pandemic…and the disproportional financial and social adversity of Covid-19’.11 With millennials set to inherit $30 trillion over the next 40 years12, this is a clear opportunity companies and investors can leverage to meet demand.

Bridging the gap

In 2015, the international community, recognising the need to safeguard the future wellbeing of our societies, launched the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs). For companies and investors alike, the SDGs offer a framework with which they can align long-term value creation with the most pressing needs of society. An estimated annual investment of US$ 5-7 trn is needed to meet the SDG’s goals by 2030; current investment in SDG-related themes is US$ 3trn per annum, leaving a US$ 2-4trn annual investment gap.

While most ESG inflows are geared toward the ‘E’ in ESG, 11 of the 17 SDG’s are oriented toward social empowerment. We believe this presents a huge opportunity for companies that can meet this need. For investors, this means bridging the financial gap by backing those companies offering social goods and services. This isn’t just about prioritising social issues, it also makes financial sense

While most ESG inflows are geared toward the ‘E’ in ESG, 11 of the 17 SDG’s are oriented toward social empowerment. We believe this presents a huge opportunity for companies that can meet this need. For investors, this means bridging the financial gap by backing those companies offering social goods and services. This isn’t just about prioritising social issues, it also makes financial sense

We believe that working towards the achievement of the social-empowerment SDGs is in the best interest of investors, as the profitability of their investments depends on the continued wellbeing of the world’s society. Failing to act on goals like social equity and resource parity may have an impact across geographies and sectors, which in turn could have detrimental effects on the global economic system.

We believe that active managers with the right analytics and engagement can leverage the investment gap that currently exists, to deliver returns and responsibility. We launched the Global Social Empowerment Strategy (GSEMS) in December 2020 to address the social megatrend. The aim of the strategy is to deliver long-term, risk-adjusted returns while also supporting sustainable global growth – by investing in businesses that provide social solutions13 – and fostering corporate improvement – via engagement and active ownership.

The strategy applies the same proven toolbox: rigorous fundamental analysis with full ESG integration, a disciplined risk management framework and engagement as a key component for fostering change. The strategy has a pure focus on businesses that provide social solutions, and uses our fundamental bottom-up ESG research platform with one of the largest dedicated responsible investment teams across the industry.

How does a strategy meet social goals?

The power of capital allocation shouldn’t be underestimated, something we have seen first-hand through our

thematic solutions, like Nordea’s Global Climate and Environment Strategy. In the case of the S factor, we see an

investment opportunity in the gap between social needs and available solutions. There are enormous needs

in areas like access to finance, access to education, affordable housing and a plethora of others. The demand

is significant, in many areas, with insufficient funding. A company that can meet these demands is in a position

to generate attractive returns. Our portfolio managers assess the profitability and pricing of these companies.

They focus on identifying mispriced assets, where the market fails to reflect potential investment returns.

Our investment team goes beyond investing in good corporate citizens, and looks for problems that need to be solved—and the companies that are solving them.

A world of social good

There is a growing recognition among mainstream market participants that prioritising values doesn’t have to cost investors their bottom line. Indeed, companies with stronger ESG practices may even perform better financially than peers with lower ESG scores. According to Morningstar, this resilience was true even during the Covid-induced sell-off.14

Historically, the ‘E’ in ESG has been the area of investor focus, with a similar story playing out in the majority of investment inflows related to the UN SDGs, leaving behind the social pillar. But the scope of ‘S’ has progressively widened over the past two decades to reflect the evolving business environment of the 21st century where companies and markets are increasingly interconnected and interdependent.

We believe there is an exciting investment opportunity behind this megatrend – and we need to act now. The outbreak of Covid-19 has unquestionably exposed the potential structural weakness of companies that don’t adequately consider the social pillar of ESG: issues like health, human rights, labour concerns, technology adoption and the management of supply chains. Given the increasingly obvious inequalities in healthcare, education and labour protection, if we are serious about building back better, then investing in companies that prioritise or provide solutions for the ‘S’ will be imperative.

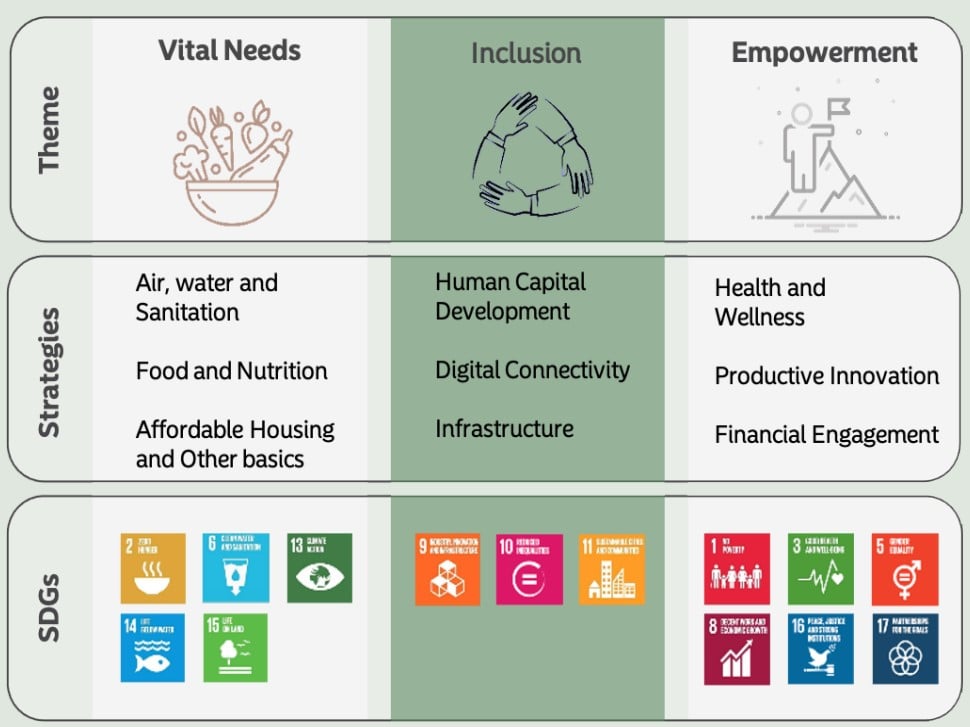

Nordea’s Global Social Empowerment Strategy focuses on three specific areas:

Vital needs

A large portion of the world’s population still lacks access to basic services that fulfil our vital needs: healthcare, energy, sanitation, clean water and nutrition. The need for these services is especially relevant in the midst of the current Covid crisis, where safe sanitation services and access to healthcare is necessary to prevent the spread of the virus and to treat the worst cases of it.

Company spotlight: Ping An Good Doctor is China’s largest online healthcare provider, with 300 million registered users. Patients benefit from 24/7 online medical services backed by an in-house medical team. More than half a billion people live in rural areas in China, where there are fewer medical resources available. Good Doctor helps to alleviate some of the pressure on the system, while boosting healthcare access to hard to-reach parts of the country.

Inclusion

Extreme inequality is another pressing social matter. Inequality in terms of access to education and the acquisition of basic social needs can fuel economic stagnation. SDG 4 focuses on quality education, building inclusive and effective learning environments. Estimates suggest that 69 million new teachers are needed to reach the 2030 education goals according to the UN. Company spotlight: The largest telecommunications provider in Kenya, Safaricom is one of the most profitable companies in the East and Central Africa region. Smartphones serve as the basic medium to connect to the internet for Kenyans, as just 12% of people have access to fixed broadband. In addition, less than 40% of the population have a bank account, but Safaricom’s mobile payment platform Mpesa significantly expands financial inclusion by enabling transactions via this system.

Empowerment

Oxfam estimates that the world’s richest 1% have more than twice as much wealth as 6.9 billion people

together. Almost half of humanity is living on less than $5.50 a day and around 735 million people are still living in extreme poverty. This significant level of inequality is triggering social unrest across the globe, leading to mistrust of governments and businesses, on top of lower economic growth.

Company spotlight: Around 20% of Indonesia ́s population are at risk of falling into poverty and do not have access to traditional financial services. Bank Rakyat provides microfinancing to small businesses that would otherwise have no access to such services. It also offers banking and savings accounts to low-income individuals, and also provides financial education.

Source: United Nations

1) Bloomberg Intelligence, ESG assets may hit $53 trn by 2025, a third of global AUM, 23 Feb 2021.

2) See Marina Apaydin et al, ‘The importance of Corporate Social Responsibility Strategic Fit and Times of Economic Hardship’ (2021) British Journal of Management, Vol.32, 399–415; Gunnar Friede et al, ‘ESG and Financial Performance: Aggregated Evidence from More than 2000 Empirical Studies’ (2015) Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, Vol.5, Issue 4, 210-233

3) Domini, Investor Statement on Coronavirus Response’ (2020) <https://www.domini.com/uploads/files/INVESTOR-STATEMENT-ON-CORONAVIRUS-RESPONSE-04.22.2021.pdf>

4) UNPRI, ‘ESG Integration: How Are Social Issues Influencing Investment Decisions?’ (2017) <https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=6529>

5) Raconteur, ‘Sustainable Investing 2021’ (The Sunday Times, 14 February 2021)<https://res.cloudinary.com/yumyoshojin/image/upload/v1613144962/pdf/sustainable-investing-2021.pdf>

6) Jacquelyn MacLennan et al, ‘Pressure mounts on EU regulator to deliver on Mandatory Human Rights, Environmental and Governance Due Diligence’ White & Case (17 March 2021) <https:// www.whitecase.com/publications/alert/pressure-mounts-eu-regulator-deliver-mandatory-human-rights-environmental-and>

7) PWC, ‘Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)’ (2020)<https://www.pwc.ch/en/publications/2020/sustainable-finance-disclosure-regulation.pdf>

8) Governance & Accountability Institute, ‘How are credit rating agencies integrating ESG factors?’ (2020) <http://www.ga-institute.com/fileadmin/ga_institute/ResourcePapers/G_A-How_are_ credit_rating_agencies_integrating_ESG_factors>

9) Jonathan Neilan et al, ‘Time to Rethink the S in ESG’ Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance (28 June 2020) <https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/06/28/time-to-rethink-the-s-in-esg/>

10) OECD (2020), OECD Business and Finance Outlook 2020: Sustainable and Resilient Finance, OECD Publishing, Paris <https://doi.org/10.1787/eb61fd29-en>

11) Peter Goncalves, ‘ESG investors prioritising climate change over diversity – research’ (Investment Week, 20 May 2021)<https://www.investmentweek.co.uk/news/4031613/esg-investors-prioritising-climate-change-diversity-research>

12) N 9 (NYU Stern)

13) According to UNCTAD 13)

14) Holly Black, ‘ESG Stocks Shine in Coivd-19 Crisis’ (Morningstar, 21 July 2020) <https://www.morningstar.co.uk/uk/news/204076/esg-stocks-shine-in-covid-19-crisis.aspx>

There can be no warranty that an investment objective, targeted returns and results of an investment structure is achieved. The value of your investment can go up and down, and you could lose some or all of your invested money.